It’s autumn, and I think it must be conference season, too. Everywhere I turn, the internet is awash with experts converging into a single wooded area or brightly-lit urban spot on the map, reciting advice, organizing workshops, writing blog posts, handing out business cards and reminding everyone of the importance of taking part in community. In other words, #community is trending.

And sometimes, this can feel lonely.

But I don’t think a weekend retreat is the only place you can grab a piece of community. I don’t think you can sell tickets for it, and then proclaim it sold-out. I don’t think our God-given longing for communion and community can be solved as easily as all that.

And this is good news for you, dear reader, you precious soul who feels left out, you who are faithfully toiling away at home or at a desk. It is good news for you who are living your life with your little family, far away from extended family; good news for you who feel alone, you who feel like you’re not a part of something special, you who feel the cries of the baby and the husband’s expectation for dinner and the demands of the children and the endless mundanity of life are keeping the ingredients for community just out of reach.

But the ingredients are not out of reach.

They are in front of you. They are front of me.

They are wherever two or three are gathered. [1]

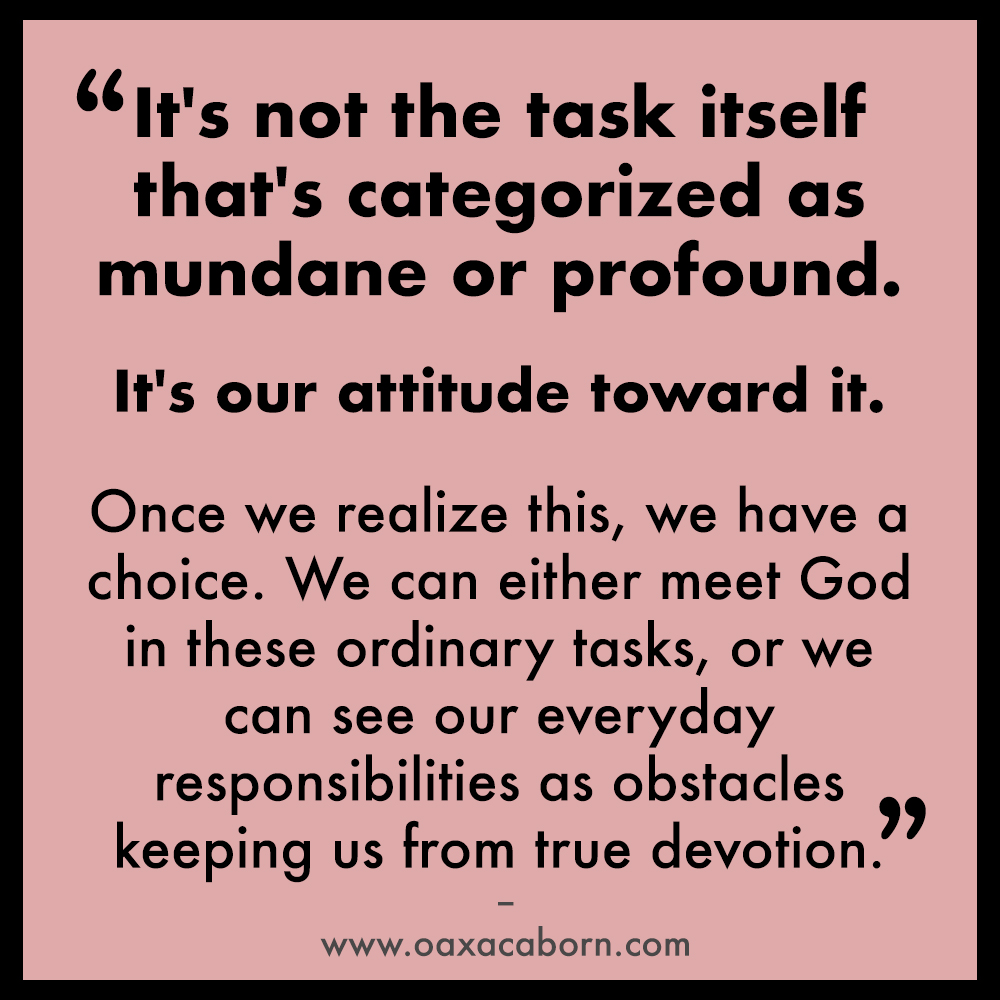

I think sometimes in our cycle of the mundane we think we can somehow capture community and rest in the quiet halls of a monastery, where the only sound is the scratch of a quill against vellum. I think sometimes in the middle of arguing with our children over lunch choices we think we can somehow capture community and devotion in the orderly schedule of an Amish farm. I think sometime we think we can somehow capture community and service in being half-way around the world, feeding the poor. But this is an incorrect perspective. We are missing something crucial. We are missing the reality that for the monastic scribe, the scratching quill and endlessly copied words are his mundanity. For the Amish mother, hanging laundry on an outside clothesline is her mundanity. For the overseas worker, stirring up another huge pot of soup is her mundanity.

It’s not the task itself that’s categorized as mundane or profound.

It’s our attitude toward it.

Once we realize this, we have a choice. We can either meet God in these ordinary tasks, or we can see our everyday responsibilities as an obstacle keeping us from true devotion.

Tozer wrote much of this secular-sacred divide, of our human tendency to see “dull and prosaic duties” as keeping us from the really important and holy tasks. He writes, “It is not what a man does that determines whether his work is sacred or secular, it is why he does it. The motive is everything. Let a man sanctify the Lord God in his heart and he can thereafter do no common act.”

He can thereafter do no common act! What a life-giving, joy-inducing truth.

Maybe you’re in a place where your children’s needs keep you from joining the latest and greatest retreat or the urgently-needed humanitarian service trip. Maybe it’s finances. Maybe it’s geography. Maybe it’s all of the above. Maybe you feel like you’re swallowed up in ordinary tasks while everyone else is off doing extraordinary things for God and for each other.

Oh, friend. Let us see these chores and responsibilities not as hindrances, but as prayers. Let our ordinary lives be our worship.

Next time everyone is off on a women’s retreat, and you are peeling potatoes — my friend, that is your offering. Next time all your Instagram friends are posting selfies with conference speakers and authors while you are folding the 37 pairs of underwear your toddler wore this week — my friend, that is your offering.

And it is no less precious.

All of your least favorite chores, all of your most exhausting battles, all your lean years where friends seem few, all the darkest of dark days — these all can be your offering. These can be be my offering. These can be our offerings. In the times when it is impossible for you to join the missionaries and the speakers and the authors and the experts and everyone else who seems to be holding out a neatly-packaged key to community, remember; you are not alone.

And can I tell you a quietly-kept secret about community? I think it’s often smaller and quieter than we realize. I think it’s already happening when two or three are gathered. [1] I think it’s less advertised, more humble, forged often more in the lonely fires of trial than in the spotlights of popularity. I think you — and I — already maybe hold all the ingredients for it. We just might have to do a little digging, a little unearthing, a little bit of getting our hands dirty, a little bit of turning our eyes back home after longingly gazing over the fence. And when we find those pieces, we’ve found great jewels, priceless treasures — here, now, in whatever quiet little place God has carved out for us.

—

Everyone has an opinion about blogging. Thirteen years ago, when I started writing online — we called it web journaling then — people didn’t have as much of an opinion.

Everyone has an opinion about blogging. Thirteen years ago, when I started writing online — we called it web journaling then — people didn’t have as much of an opinion.